THE BIVY

Bivies were, and still are, mostly used as emergency shelters by mountaineers. However, some backpackers see them as a viable (and lighter) alternative to a tent or tarp. I was one of those folks.

Bivies have been around for a long time. Basically they are a waterproof envelope or a big bag you put your sleeping bag inside, eliminating the need for a shelter. I bought my first bivy some 30 odd years ago. Designs haven’t changed much since then. Years ago you could get a basic bivy that weighed around a pound. And you could, just like today, get a bivy with an elaborate setup at the “head” end using poles or a hoop to provide a little more room at the top of this most minimal of shelters – you could lean on your elbow and move around a bit. These fancy bivies, just as they do today, generally weighed at least twice as much as the basic bag.

Back then, as today, most bivies were waterproof (I will discuss the newer exception a little later). Some are made from waterproof/breathable (WPB) materials. Just like the futile search for truly breathable rainwear I wrote about in The Search for the Holy Grail, bivies suffer the same inability to breathe well. This failure, when it happens to bivies in cold weather, means condensation on your sleeping bag and sometimes, when conditions are right, a wet sleeping bag.

One strategy to eliminate condensation is to place a light bag inside the sleeping bag made of completely non-breathable material. This way no water vapor escapes from your body and into the sleeping bag, meaning condensation cannot form on the sleeping bag, and your sleeping bag stays dry. We call this non-breathable bag a vapor barrier liner or VBL. What seems like a simple solution is not so simple. VBL’s are tricky to use for most people. Ambient temperature really needs to be well below freezing or you will get hot and covered in perspiration. And of course, they add weight to the sleep system.

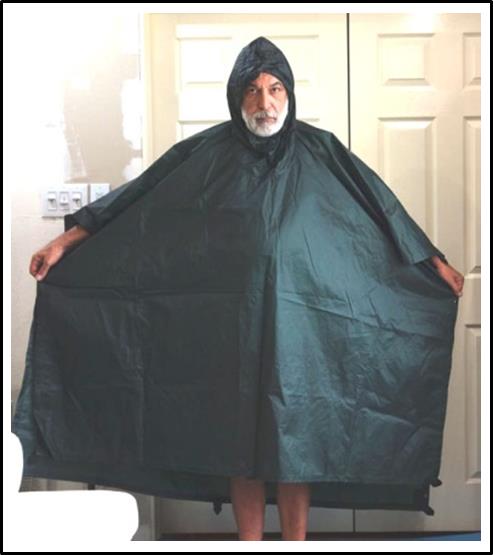

Above: Vapor liner, sleeping bag and bivy combo.

THE COFFIN

I find bivies to be claustrophobic. Plus you cannot cook, change clothes, or even sit up to read a map in one. You can’t sort or organize your gear, because there is only room for your body in the bivy. For backpacking, a bivy as your only shelter is an idea that fails in the field for most people. I suppose there are backpackers who get by just fine with a bivy as their single shelter.

Over the years I would occasionally re-visit the bivy solution. And always with the same result – I hated it. You know the old saying… doing something over and over and hoping for a different result.

Keep in mind, I would only use the bivy if the weather was bad, otherwise it would stay in my pack and I would sleep under the stars.

TARP

I have always preferred a tarp over any other type of shelter. They are light and versatile. For forty-something years I used two kinds of tarps:

(1) A 8’ X 10’ flat tarp that could be set up in many configurations.

(2) A 5’ X 8’ poncho/tarp that could be used as a shelter and rain gear.

For shorter trips where a chance of rain was in the forecast or (often) in deserts I would get by with just the poncho/tarp. On long trips or when rain was in the forecast I would take a large tarp and the poncho/tarp. The tarp would be my shelter, the poncho my rain gear and sometimes double-duty as a groundsheet.

PONCHO/TARP DRAWBACKS

The poncho/tarp has a couple of drawbacks. First, if the weather gets downright nasty, it is hard to stay dry. Pitching it low to the ground would increase coverage, while decreasing headroom – almost getting to the point of a bivy where there is no room to cook, organize, or change clothes.

The second drawback to a poncho/tarp is how do you set it up as a shelter, if it is pouring rain when you arrive at your campsite, with your shelter on your body – as rain gear. You will get wet!

Over time, the experienced poncho/tarp backpacker learns how to handle both shortcomings, and can stay dry most of the time. Sometimes he or she will just opt to bring a large tarp, especially when inclement weather is expected.

EVOLUTION OF THE BIVY FOR BACKPACKERS

In 2008 or so, I bought a water resistant/breathable bivy (NOT waterproof). The bivy was quite light; the goal was to provide a little more extra weather protection under a small poncho tarp without having to worry about a lot of condensation.

This system worked very well for most trips. Spending time in the bivy under the small shelter was not super-pleasant in prolonged nasty weather, but overall it was a good system. It helped protect my sleeping bag or quilt from the water that would somehow get under the small poncho/tarp. At only 16.7 ounces for a shelter and rain gear, I was a happy camper and backpacker — most of the time. I became a poncho/tarp & bivy advocate — for most 3 season trips.

But there were still times when a larger tarp was the best solution, especially when the temperature got down to the dew point and condensation would build up between my sleeping bag/quilt and sometimes the down would get wet. This is a potential disaster in really cold weather.

Cuben Tech

This material is light, strong, but not very abrasive resistant. Originally it was used for sails on racing yachts and slowly made its way in the backpacking world. It is expensive and requires special skill to make gear out of it; you just can’t sew it like nylon or other materials. It took some time, but a few small cottage industry manufacturers got good at building shelters out of Cuben Tech.

Bivy Not Included

A few years ago I took the plunge and bought an 8’ X 10’ Cuben fiber tarp that weighed only 5 ounces. The tarp was almost twice as large as my poncho/tarp, so the added protection of a bivy was no longer needed.

I also ditched poncho for a lightweight Waterproof/Breathable (WPB) rain jacket that weighed right a 6 ounces. Because the large coverage of the tarp eliminated the need for a bivy, I now had a large shelter and rain gear with a total weight of 11 ounces or so, which cut almost 7 ounces from poncho/tarp & bivy system – almost a 50% reduction in weight.

A Day at the Races

I was thrilled. But reality set in. I had purchased a WPB jacket. I knew better. I knew it was hype and all the claims of improved materials and venting were fairy tales, I knew the “fan boys” who swear by these new garments were wrong, I knew the reviewers were liars – but I bought it anyway.

- And then I took it on a backpacking trip where it rained most of the first day.

- And it made me sweat profusely as I climbed uphill all day.

- And then it leaked rain from the outside because the laminate was overwhelmed with perspiration – I was soaked from the inside and the outside.

- And the ambient temperature began to drop; significantly.

- And now hypothermia would be a problem if I didn’t get warm soon.

So I stopped, set up the new big Cuben tarp, got into dry clothes, got into my quilt, and made some hot soup. The tarp was a success, the jacket a failure.

Cuben to the Rescue, again

Another drawback to the poncho/tarp is it is big and billowy as rain gear.

Oh, it is nice that the poncho can cover your backpack too, eliminating the need for some sort of pack cover. It is bigger than it needs to be for rain gear; and it really is sort of small as a shelter. As the saying goes, “Jack of all trades, master of none.” This is how it is sometimes with multi-purpose gear.

So I still needed a rain gear solution and I found the newly released zPacks poncho/groundsheet. Perfect size for a poncho. Made from Cuben. Light at 4 ounces.

It has been my hiking rain gear since around 2010.

Combined with the 5 ounce full size tarp, I had a shelter and rain gear for a total of only 9 ounces. Sometimes I would opt for my heavier shaped tarp, called a “Mid” that adds a couple ounces.

I am happier, drier, more organized in camp, and my pack is lighter.

ARE BIVIES OBSOLETE?

For the backpacker who wants to supplement his or her shelter with a bivy, I would generally say the bivy is just a Band-Aid for an inadequate shelter or other gear. You (and me) are trying to compensate for a poorly designed shelter for the conditions you are in.

- If you need a bivy because your sleep system is touching the walls of your shelter, then your shelter is too small.

- If you need a bivy to stop wind from infiltrating your quilt or to add additional warmth to your sleeping system, your sleeping system or shelter is inadequate.

- If you need a bivy as a groundsheet, there are lighter options, such as polycro.

- The only thing left to address is mosquitoes and bugs. Unless you hike in Alaska or Minnesota, which are the only two states I have not hiked in, at the height of bug season you can get by with a headnet and a quality woven nylon shirt and trousers. I find the bug netting in bivies to be awful. I have never owned one of those “inners” that are netted shelters that set up under a tarp or shaped tarp — for me they would just be extra weight to carry around.

- Most quality sleeping bags and quilts these days are constructed with water resistant fabrics. A water resistant bivy isn’t going to help. A waterproof bivy is worse. It is better to get a larger tarp that doesn’t require a bivy-bandaid — get a shelter that won’t allow water to spray onto your sleeping bag.

- There are lighter and more efficient systems than the poncho/tarp and bivy solution.

However…

There is a certain appealing attraction to an inexpensive poncho/tarp combined with a breathable water resistant bivy. First it requires practice and skill to stay warm, dry and safe; and it can be a very inexpensive and lightweight solution. My Cuben fiber alternative is expensive and only saves a few ounces, but it does make me more efficient in the wilderness.

With a silnylon poncho/tarp and an economically priced water-resistant bivy, you can assemble a really lightweight shelter and rain gear solution for around $200. Keep in mind that there is a higher level of skill, knowledge, and experience needed to be successful with this combination versus and rain jack and a conventional shelter.

Take your pick

If either method appeals to you, whatever you choose is a good choice. There is no right or best way; there is only what works best for you.