You don’t have to be a genius to know that the lighter your backpacking kit is the easier it is to hike. The easiest way to lighten your load is to discard things you don’t need, get rid of duplicate items, and opt for items made from lighter weight materials. Often gear can be jettisoned and replaced with skill alone.

At some point the parring down process reaches a point of diminishing returns and can enter the realm of “stupid light” as described by well known adventurer Andrew Skurka.

Today I hear many backpackers, who are trying to lighten their gear, ask, “What is the best pack that weighs less than X ounces?” and often that request for input that has an arbitrary formula such as:

X <= 16 ounces

One might wonder what rationale or unfounded thought process brought these folks to the conclusion that X ounces is the defining criteria for a piece of gear. It is the concept that less is more, or the lighter your pack the more enjoyable your trek will be. That may be true to a point, unless you cross into stupid light or into the kingdom of diminishing returns where weight compromises comfort and efficiency.

Less is more is an oft quoted concept of the modernist architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. What it means is good design is dependent on focus and simplicity. The corollary proposition to this concept is the modernist architecture mantra of form follows function. The shape or design of an object must be based on its function or purpose, not some random goal such as a specific weight as the only consideration.

How did we get to this point where pack weight trumps function? We can blame Don Jensen, Dana Gleason, Wayne Gregory, Ray Jardine, and a multitude of other pack designers.

REVOLUTION: 1950’s & 1960’s

In the 1950’s Dick Kelty revolutionized the modern backpack with his curved aluminum tube external frame and nylon pack bags. Kelty packs, which weighed less than 4 pounds, were widely imitated by other companies. These modern marvels supplanted the wooden pack frame, the most famous being the wood and canvas Trapper Nelson.

The drawback to these packs was all the weight was carried on the hiker’s shoulders, shoulders that are not up to the task of carrying heavy loads and can lead to sore muscles, pinched nerves and other discomforts. There is even a medical term for this, backpack palsy. Compounding this is the fact our spines are not designed to support these loads. The solution, often credited to Kelty or sometimes his competitor Trailwise (take your pick) was to add a hip belt to the pack and transfer most, if not all, of the weight to the hips and legs, which handle the load more easily and efficiently. The shoulder straps’ function now becomes one of keeping the pack close to the body and from shifting while hiking. And it works exceptionally well.

Moving the weight from the shoulders to the waist was not a perfect solution. Early belts were simple web construction and more often than not, caused pressure point pain on the hips and even bruises. Dick Kelty somewhat overcame this deficiency with a padded wrap-around hip belt. Not perfect but far better. Eventually the hip belt would perfected by Dan McHale.

THE NEW WAVE: 1960’s & 1970’s

These aluminum framed packs became extremely popular in the 60’s and 70’s with one exception – they weren’t ideal in off-trail and mountaineering conditions. They weren’t kept snug against the hiker’s body and could shift or move at the most inopportune times. To solve this, pack makers started to place the frames inside the pack, using bendable strips of aluminum called stays. These were simple rucksacks with aluminum stays, the first being manufactured in the latter 60’s by Lowe Alpine.

In the late 60’s Don Jensen designed a frameless pack with a belt, which used two “tubes” of material to tightly pack the hiker’s gear creating a virtual frame. Rivendell Mountain Works sold these as the Jensen Pack starting in 1971, followed by The North Face, Gregory Packs, and the well known Chouinard Ultima Thule pack. The problem with these frameless packs was if they weren’t packed perfectly and with enough gear the structure would collapse and all the weight would be born by the shoulders.

In 1973 Kelty released the first full-featured internal frame pack with an integrated waist belt suspension system, the Tour Pack, which was soon copied by many pack companies. The difficulty with these packs was they weighed more than the external frame pack popularized by Kelty.

FEATURE CREEP: 1980’s

By the early 80’s Wayne Gregory of Gregory Packs and Dana Gleason of Dana Designs were selling feature-rich behemoth internal frame packs that weighed double that of their external frame counterparts. And hordes of hiker’s rushed out to buy them after backpacking guru Colin Fletcher revealed, in his book The Complete Walker III, that he had retired his beloved Trailwise external frame pack, replacing it with an internal frame Gregory Cassin pack. Fletcher sold lots of books and Gregory became rich and famous.

Lightweight in the 80’s

In the 80’s while the Fletcher faithful were stuffing their large volume internals to the brim, many of us continued to hike with our lower volume, lighter external packs. We were the ultralight hikers of the era, and many of us would do short of weekend trips with all our gear in a simple rucksack, light enough so we wouldn’t get backpack palsy.

1990’s THE SO-CALLED ULTRALIGHT REVOLUTION

In 1996 Ray Jardine re-popularized lightweight backpacking in this book, Pacific Crest Trail Hikers Handbook, by advocating light frameless packs, tarps instead of tents, and other weight saving strategies – none of which were new or revolutionary to many hikers. Ray was smart and knew that a hiker can’t carry a lot of weight in a frameless pack and was a proponent of frequent re-supply stops on trips; not my perception of a wilderness experience – stopping every few days for food and supplies. I call the Ray Way of hiking boutique hiking. But many people see a light frameless pack as lightweight Nirvana.

FRAMELESS PACKS

There is elegance in simple frameless packs, and to me this elegance is a minimal stuff sack with shoulder straps. No hip belts, no mesh pockets, no shoulder strap pockets. I often do short trips of 2 or 3 days with this type of pack.

However, I find that when the total weight of the pack exceeds 12 pounds, it is uncomfortable.

That is my threshold; others say they can be comfortable with 20 or even 30 pounds in a frameless pack. Like the attempt to create virtual frames in the Jensen packs, these hikers try to stiffen their pack’s contents by inserting a rolled foam pad inside the pack, stuffing gear into the center of the roll like a burrito. Other methods such as using external compression straps to squeeze all the gear is another. Bottom line is that if there is too much weight or not enough gear placed perfectly, the virtual frame collapses and the backpacker is back to the carrying all the weight on his shoulders.

If you are boutique hiking, I suppose you could keep your total weight down around 20 pounds on an extended trip using frequent town stops to replenish food and consumables like stove fuel. For me, no thanks.

THE RIGHT TOOL FOR THE JOB AT HAND

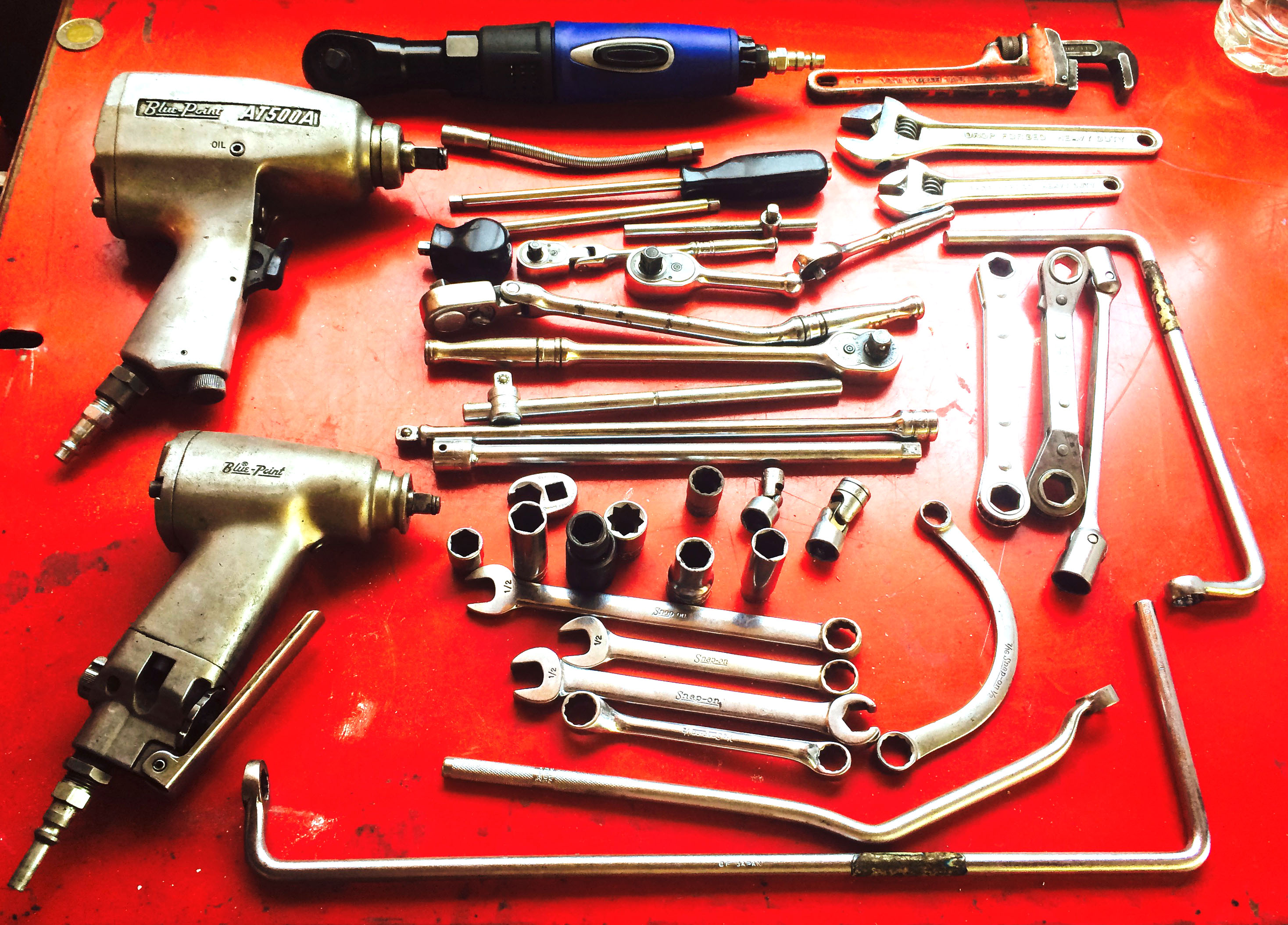

For many years I was an auto mechanic. I was paid by the amount of work I did each day. The more jobs I could finish, the more money I made. To be quick, efficient, productive, and ensure quality work I found it necessary to purchase specialized tools; tools that allowed me to complete a repair or service a vehicle in minimum time.

Before the Commies and Socialists forced us to use metric fasteners, a 1/2” wrench or socket was a common size tool. The picture above shows many options for removing a nut or bolt that requires a 1/2” tool. It’s about using the best tool for the job at hand. The same holds true for a backpack – the right pack for the load, location, and weather. One could just use a single large pack for all possible scenarios, but most hikers find it better to have 2 or 3 packs that cover most trips and conditions they will encounter.

INTERNAL FRAME PACKS

Most of my trips I use either a McHale Bump pack or a larger McHale Little Big Pack (LBP), both of which have robust internal stays made from 7075-T6 aluminum.

The stays can be shaped to the contours of my back and will not compress under load, like the inferior frames used in most “ultralight” packs made today. When a frame compresses the load shifts from your waist to your shoulders, which is undesirable.

At 20lbs of weight, my McHales are much more comfortable than my frameless pack. At 30lbs – no contest, the McHales are top notch performers. And nothing on the market can touch my McHale LBP at 40 or more pounds. Now, 40 pounds is a lot of weight, but if you want a wilderness experience provided by a two week trip where you are unlikely to see anyone else, you will need to carry a lot of food. Add some water and you will easily hit 40 lbs.

Not only do the stays transfer the load to my hips without compression, the design of the hip belt alleviates any pressure points and the belt does not slide down when hiking.

Critical Success Factor: Fit

Most internal frame packs come in 3 sizes; small, medium, and large. If your body happens to fall into a happy niche of these sizes your pack might fit okay. Most of these sizes have a torso length range of a couple inches or more, so say the manufacturers. A couple inches often equates to a poor fit, which in turn equates to a miserable hike. The correct approach is to buy a pack whose frame and belt exactly matches your body – meaning for most people – a custom built pack. As far as I know, there is only one person who builds packs with a custom fit – Dan McHale. Of course, custom anything includes a premium investment on the buyer’s part.

FORM FOLLOWS FUNCTION

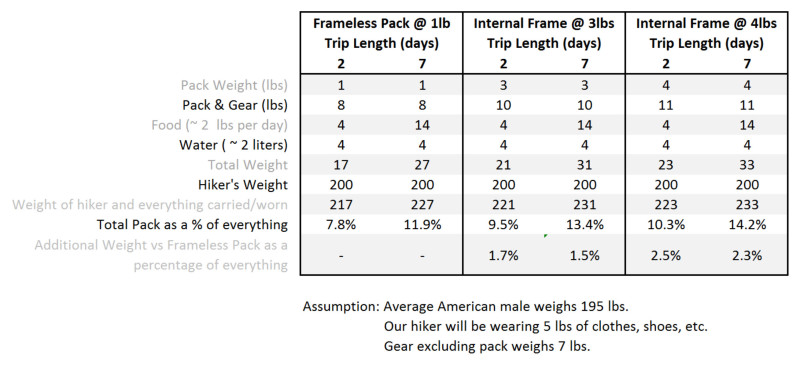

A hiker’s pack is his house on his back. It is the foundation and structure of everything he carries. The hiker spends most of his days carrying the pack. In most cases a frameless pack does not function well, especially given the hiker is only sacrificing a couple percentage points of the total weight his legs need to carry, and suffers a substantial reduction in carrying comfort. The table below shows how little impact a 3lb or 4lb pack has versus a 1lb pack.

Why?

Why are so many backpackers fixated on the weight of their pack instead of comfort and ultimately everything they are carrying? Mostly because they are spreadsheet backpackers, sitting at home and posting gear lists to online forums. It’s about bragging rights.

There is nothing wrong with lightening your back as much as possible. I do it. I also use a frameless pack when it is appropriate. On some trips all my gear plus clothing worn can go below 5 lbs. total. But these are for specific trips where it makes sense, not what I do most of the time.