Writing backpacking trip reports can be a pain in the ass. If I wrote a report for every trip I did I would probably quit backpacking or quit writing. However, it is a semi-tradition for me to write a lengthy report for my kids at the end of each year.

So this is the 2014 version.

Since I live in a desert, my favorite backpacking months are November and December. Weather can be variable, but not a detriment to taking a trip. And one of my favorite places is Anza Borrego State Park (and adjoining Federal Wilderness Areas). Navigation can be tricky or down right difficult; there are no trails and lots of canyons that make navigating akin to wandering in a maze. In December rain, flash floods, and potential snow keep most people away from the places in Anza Borrego I like best. Additionally permits are not needed – no Government bureaucracy to deal with.

This year I decided to do a 4-day trip the week before Christmas. Anza Borrego was the destination.

Contrary to the itinerary I left with Joyce, I decided about 2 hours into the hike to detour to the Mojave Valley, which is above Rockhouse Canyon. Rockhouse Canyon gets its name from the ruins of Native American rock houses in the area above the canyon. There are a couple springs with available water if one knows where to look, so it is always a good backpacking destination for me.

Over the past couple of years I have been loath to discuss gear, but I will break that rule for this post.

BATTERIES!

As you probably know, I try to avoid battery operated gadgets in the back-country. Batteries go dead; electrons get scattered; the technology removes us from wilderness as I wrote here. I usually take a watch, and these days it has a battery. The watch keeps me on task so I return home on time, so Joyce doesn’t call the rescue cavalry. When trips get into the 4+ day range I sometimes forget what day it is and a watch is mandatory if I want to get back at the promised time and place. These days I almost always take my inexpensive Timex Expedition watch, as I wrote in this watch post. Strapping on the watch before leaving for my trip, I noticed the time was wrong and the second hand wasn’t moving. Drat! Dead battery. I am not in the habit of winding a watch each day, so the military watch in my drawer was out.

I decided the best bet was the solar powered Casio PAG watch Joyce bought me a few years ago. It has an altimeter that has to be constantly adjusted, so it is worthless to me. Plus on this trip I decided not to take a map – sometimes it is nice to figure out without any aid where you are, and since I am familiar with my destination, mapless has a certain appeal to me. Without a map to calibrate the watch’s altimeter function, it is of no use.

The watch also has a thermometer, but it senses your body temperature. You have to take it off and let it sit for quite a while to accurately measure the ambient temperature. But who needs to know the temperature? Either it is too cold, too hot, or perfect.

The watch’s redeeming features are it is rugged, time is accurate and the battery doesn’t go dead since it is solar powered.

The next battery failure would be my headlamp on night 3. I guess I should have put in fresh batteries; the ones in it were old. Can’t remember the last time I used it. I think it was in 2013 on the Appalachian Trail. Anyway, it is a bad idea to leave batteries in gadgets for extended periods of time. The death of the headlamp batteries was a minor inconvenience.

The last battery failure would be my camera on day 4. I guess I should have checked it too. A camera isn’t necessary for a successful trip, but the kids like pictures.

DAY 1

My trip started at the base of Alcoholic Pass. I have written about this route before. If you are interested, you can type Alcoholic Pass in the search box thingy at the top of the page of other trips I have done in the area. As I neared the top of the pass, I saw a bighorn ram in the distance. Waiting and stealthily moving about I was finally able to get close enough for a picture.

Eventually he left the area and I continued down towards Clark Dry Lake. It was at this point I noticed the camera battery was only 25% charged. This was probably a blessing. It would limit my enthusiasm (or perceived need) to take a bunch of pictures.

It had rained several times during the weeks before this trip and the sand along most of the hiking would be somewhat compacted making it easier than normal; dry loose sand can really slow down progress.

Rain was forecast for the afternoon and evening. Because the weatherman is not always accurate, a little deterioration could result in snow – not predicted, but wise to be prepared.

The Smoke Trees in this unnamed wash have perked up after the recent rains. The sand is nice and firm making progress quicker than usual.

Out of the wash I am headed cross-country towards Rockhouse Canyon. The ever-present clouds are a reminder that washes can be dangerous due to flash floods. Most flash floods occur in the summer, but one must still be cautious all times of the year.

For this trip I took my favorite piece of backpacking gear, the McHale LBP 36. It is rugged and comfortably carriers copious amounts of water and food. McHale packs can be ordered in any color combination imagined, but I choose a scheme that blends into the desert environment. Over the past 4 years the almost bullet-proof Dyneema fabric has softened to a pleasant texture. The only maintenance required is to wash it once in a while. If not, salt builds up from sweat and little rodents like to chew on the salt.

At Hidden Springs, Rockhouse Canyon begins to close into a narrow steep walled course. The sky looked like it was going to rain soon and best judgment was to detour out of the canyon up to Jackass Flat.

Most of the year, Hidden Springs is just a seep and often infested with bees. The water is not very good either. Since I had a gallon of water with me, and with cool temperatures I could probably stretch the water supply out for 3 days, including water for cooking meals. Most people need more water, but living in the desert for almost 40 years I have adapted to need less water than most.

Most of the year, Hidden Springs is just a seep and often infested with bees. The water is not very good either. Since I had a gallon of water with me, and with cool temperatures I could probably stretch the water supply out for 3 days, including water for cooking meals. Most people need more water, but living in the desert for almost 40 years I have adapted to need less water than most.

Above: Rockhouse Canyon begins to narrow. Notice that the soil is hard packed from recent rains, so a downpour would mean the canyon floor could absorb very little water, a good formula for a flood condition.

To get out of the canyon I would have to climb up this 200 foot wall. The best method is to stand back and look for a route that is most efficient. In this case it would be to travel right to left. Since I have climbed this many times, I know there is a faint footpath probably created by hundreds of years of animals and Native peoples walking the route. There is no real trail; no signs; no cairns. It only took a few minutes for me to get to the top.

From the vantage point above Rockhouse Canyon on Jackass Flat, I knew I made the right decision to leave the canyon.

Turning away from the canyon, the skies were already dumping rain and I could see it rapidly approaching. I quickly donned my poncho, located a nice open and well drained spot, and began to set up my shelter. On most trips I take my minimalist zPacks Hexamid shelter. For this trip I was expecting rain, possibly snow, and lots of wind. Plus nights are over 12 hours long. Lastly, I had started writing an article during my Thanksgiving Bike Tour about my 500 mile Mojave Desert Hike in 2000 that I wanted to continue working on. Given all these factors, I brought my roomy and wind-worthy Trailstar shelter for this trip.

Setting up in the rain is mostly the same no matter what shelter I bring. Here are the steps:

- Put on rain gear (a poncho in my case).

- Take out the shelter, which should be packed at the top of the backpack for quick and easy access.

- Erect the shelter.

- Put the pack inside the shelter and crawl in. A large shelter like the Trailstar makes this easy.

- Lay out a ground sheet. In my case a 1.6 ounce polycro film from Gossamer Gear with dimensions of 40” X 96.” I don’t always bring a ground sheet, often preferring to just use a waterproof foam pad. But I knew there would be lots of moisture in the ground, so the ground sheet would help keep things dry and neat.

- Place the foam pad on top of the ground sheet. I use a 1/8” thick pad mostly to protect the air mattress. Unlike most people, the past couple of years I have gotten into the habit of folding the foam pad and storing it inside my pack. No rolled up pad to attach outside of the pack where it can catch on errant brush and cacti.

- Blow up the air mat. In recent years I have switched from thicker foam pads as my only ground insulation and padding. It is a concession to getting older. At 64, I feel entitled to this little Air mats, like my Cascades Designs NeoAir, have gotten incredibly light. No, I don’t have some sort of pump to fill it up with air. I inflate it the old fashioned way. I blow it up.

- Inflate the air pillow. I used to use shoes or clothes as a pillow. A few years ago I bought an Exped air pillow. Light and much more comfortable.

- Fluff up the quilt and lay it on the air mattress. The bed is done. Now I have a nice soft place to sit.

- Change into warmer clothes. I had been hiking in shorts (Patagonia 5” Baggies my favorite for decades) with the liner cut out to save weight and give the nether regions ventilation, and a light merino/poly blend long sleeved T-shirt. With the temperature quickly dropping and no longer actively moving, I removed the shorts and pulled on a pair of Patagonia Capilene 1 lightweight bottoms and then my uber-light Montbel Dynamo wind pants. I always just leave my merino wool socks on, unlike many backpackers who bring an extra pair of sleeping socks, which is a weight penalty that I substitute for the air pillow. I also leave my hiking top on and in this case, put on my Montbel Ex Ultralight Down Jacket. A Smartwool brand merino wool beanie on my head and a pair of Possum Down gloves complete the ensemble. I also take out my 1.6 ounce goose down hood, which I will wear when I go to bed, since my quilt doesn’t have a hood.

- Organize gear for the night. Take out the headlamp; position my water bottle for easy access. Assemble my Caldera Cone stove and take out the night’s meal from the Cuben food bag. On most trips I use the “Freezer Bag Cooking Method.”

Within minutes of setting up the shelter, it rained hard. Here you can see the drips on the edge of the shelter and the beaded rain drops on the silnylon material.

The wet outside world as viewed from my dry and comfortable shelter.

After dinner the rain subsides a little and I go for a night walk. Returning to my shelter I write a little and then settle in for a good night’s rest.

DAY 2

I awake around 6:00am and there is a steady rain outside. I think to myself that I hate taking down camp and setting out for the day in the rain. So I go back to sleep. I awake at 8:30 and the rain has stopped.

The sun is out and breaking camp will be a pleasure. Today the sunshine will be short lived and clouds and light rain will return later in the afternoon. After eating breakfast and enjoying a cup of coffee I get up and go outside to have a look about and to see how my shelter held up. Most silnylon shelters tend to stretch and sag after a night of rain and wind. What I like about the Trailstar is that, even though it is made from silnylon, it keeps its tension overnight.

Most hikers use a pair of adjustable trekking poles to erect shelters like the Trailstar. I have mentioned before that I don’t care for trekking poles. For the center pole of the Trailstar I use a .600” diameter adjustable carbon fiber from Ruta Locura that weighs less than 4 ounces. For the outside pole I am using a Black Diamond Alpine Cork adjustable trekking pole. The pole does double duty as a walking staff on trips like this where I am climbing slopes, washes, boulder fields and other obstacles. When I don’t need a walking staff I have another Ruta Locura pole for the outside Trailstar pole. My zPacks Hexamid only requires a single pole and I use a .450 diameter, 48” fixed length pole also from Ruta Locura. The tension of the Trailstar requires a more robust pole, thus the .600 versus .450 inch diameter.

It is route decision time.

Jackass Flat drains into Butler Canyon and to the north and east is the watershed for Dry Wash Canyon and Box Canyon. In between is a rugged mountainous area that runs above both Butler and Box Canyons. To the west of this the mountain, it drops down into Collins Valley. The only easy access to this higher altitude section is via Butler Canyon, the route I would normally take. There is only one easy route off into Box Canyon should one chose that at all costs (voice of experience speaking here). Dropping down into Collins Valley from this mountainous area is very difficult.

I have never climbed up via Jackass Flat. My son Joe and I tried this route in 2008, but white-out snow conditions and an injured knee on my part made that route too difficult.

Joe in 2008 before the weather deteriorated.

So I decided to take the route Joe and I started 7 years ago. Even though I didn’t have a map, I knew what my strategy should be.

I should note that not taking a map is not as drastic as it seems. I am extremely familiar with the area, except for the one section I would hike today. I had my compass with me and there was plenty of time to back-track if the way proved too difficult, which was unlikely due to my knowledge of where I was headed.

Once I left Jackass Flats, I needed to stay south close to the mountain. Most hikers tend to drift towards the right to Dry Wash, a very difficult area that is in the opposite direction I needed to go, although once in the area Dry Wash’s direction is deceiving. This part of the desert is very easy to get disoriented in. I also know that once I saw the top of Box Canyon, I would need to climb up the mountain in a southwardly direction. Like the need to avoid Dry Wash, I definitely didn’t want to try and descend Box Canyon from its beginning. The Box Canyon in this area is not the same as another Box Canyon that was part of the Emigrant Trail, and is also in Anza Borrego. Anza Borrego is so big that there are many areas with duplicate names.

There would be several ridges and valleys to ascend and descend, but eventually I would get to areas I would recognize from past trips. I also knew the walking would be slow, but I had time.

In the end, this route was fun but the scenery wasn’t outstanding. A descent into Butler Canyon and then an ascent up and out of Butler Canyon would be more pleasant hiking country, but I have hike that many times. However, I am glad I did this alternative routing.

Above: leaving Day 1 night camp and heading through a Cholla Garden.

In the distance it looks like the upper elevations (Toro Peak) got some snow the previous night.

The morning saw the sky beginning to get overcast and would continue to do so for the rest of the day. Good for minimizing water consumption, not particularly good for hiking cross-country without a map.

I finally got close to the upper entrance to Box Canyon and started my climb up into the hills where the travel became more challenging.

Boulders and thick vegetation makes for slow going. I needed to go slow and careful. It would be next to impossible for anyone to find me here should I get injured. I found a spot void of vegetation and decided to stop and remove a couple small pebbles from my shoes. For those who read my blog often, you know I am a big advocate of minimalist shoes for hiking. But they are not appropriate for this kind of terrain. For me the Salomon XA Pro 3D is the perfect trail running show for desert terrain like this. I think I am on my third pair. I have a couple more new pair at home, since shoe companies have a tendency to discontinue great shoes. Even in this environment I get over 500 miles out of a pair of XA Pro 3D shoes.

Up hills and over ridges and descents. Do it again. And again. I finally arrived at a plateau overlooking Butler Canyon. I recognize this place. Time to head westerly over a pass and I would descend into a playa. Cross the playa and cross another ridge leading down into a larger “L” shape playa. I knew where I was and where I needed to go. When I got down to the 2nd playa it began to rain. Not good timing. It would be necessary to hike across the playa, which would become a pond if it rained too much, and at the end of the playa I would need to hike up a steep wash several hundred feet up to a pass that overlooks the Box Canyon drainage. There was nothing to do but get out my rain gear and push ahead before it rained too much. My favorite rain gear, as I wrote in the Search for the Holy Grail, is a Cuben fiber poncho and a Cuben fiber rain skirt, both made by zPacks. The climb out of the playa, up the wash to the pass, was going to test the gear for water proofness, breathability, shrubs and cacti – but I was confident; it had never failed me before. One concern was I had never used the poncho over my McHale LBP 36 backpack; something I thought about at this point in time – not before the trip. The poncho is cut small – not billowy like most ponchos. I put on the rain skirt which covered my thighs just above my knees. It would keep my hiking shorts dry. I pulled the poncho over my head and then pulled it down and around my torso and the pack. I was able to zip up the sides of the poncho and it fit almost like a jacket around me and the pack. Not too tight to restrict movement, and tight enough that it was unlikely to catch on branches. Perfect!

Away I went. The rain was steady, but fortunately light. Across the playa. Up the wash. The steep boulder strewn plant infested gauntlet of a wash. Add the water trickling down and the slick rocks requiring stepping on, it could have been the perfect recipe for an accident. I walked cautiously watching the placement of each step, thankful I had the third leg of my staff to help steady my progress. Watching each step was pleasant, a micro view of my world. Soon I was at the top of the pass. And I was dry. Very dry. Absolutely no sweat. Again, the poncho proved its value over all other kinds of rain wear.

The next goal of my life was to find a spot large enough for the Trailstar and in a location that would drain any rain accumulation. A daunting task in this place. I had about two hours of daylight, but I would only hike until I found the perfect campsite, not until it got dark. Good news was that the sky was clearing and the rain had stopped. I took off the rain gear. About 30 minutes before sunset I found my perfect camping spot. The top of a slightly sloping hill with good drainage. It was the only place in my immediate vision large and flat enough for the Trailstar.

A repeat of the previous night’s set up. Once inside the shelter the wind started. Wind is no enemy of the Trailstar, which is why I brought this particular shelter that weighs almost 3 times as much as my Hexamid; but only 22 ounces.

The night was uneventful, but I could hear the wind. The shelter barely flexed as the wind tried to shake it. I was able to sleep without being cognizant of the blustery weather and in the morning the gale was still pounding. Like the previous morning when I thought about breaking camp in the rain, this morning my thought was, there is nothing worse than breaking camping in the wind. Or is rain worse? No, wind is. I packed everything into my backpack, except my windshirt which I put on. Moving the pack outside, I fought the wind for control of the shelter as the wind tried to rip it from my hands. Final score: Me 1, Wind 0. I left with a bit of trepidation. I would have to hike a long ridge down into Box Canyon. Been there, done that in windy conditions. The force can knock you off your feet. If you don’t fall down a slope to certain injury, the wind can blow you onto some nasty cacti. Oh well, no choice but to move forward and hope for the best. Within 30 minutes the wind stopped and it became too hot to hike in the windshirt. The sky was blue with wisps of white clouds. I was so happy with this change of events that I hiked to a couple areas I had not explored yet.

After checking out these places, I crossed two ridges and found the route leading to the bottom of Box Canyon. In the picture below I would follow the ridge in the lower left to the hump in the center. Below the hump, I would descend right to the side canyon below the hump and take it to the main Box Canyon.

There is an ancient foot path along the ridge and then down. It is barely visible, but I have hiked it several times. Hiking through a section of thick cacti I had my only “mishap” of the trip: a cholla caucus pod kicked up by foot imbedded itself in my leg. Ouch! About a dozen stubborn spines refused to shake loose. Carefully cutting each of the spines with a razor blade (my definition of a knife), the pod fell to the ground. I pulled out each spine with my finger tips and was soon mobile again.

Once I got down into the side canyon’s wash, I noticed a large boulder where the trail ended with an apparent petroglyph on it. I had never observed it before. Is it a sign that the trail up starts here? It is a Swastika, a common sign used by Native Americans. What does it really mean? Is it authentic or a recent piece of graffiti by some skinhead? I don’t know, but I think it might be old enough to be considered an authentic piece of rock art.

Hiking down Box Canyon is always pleasant, one of my favorite locations to walk.

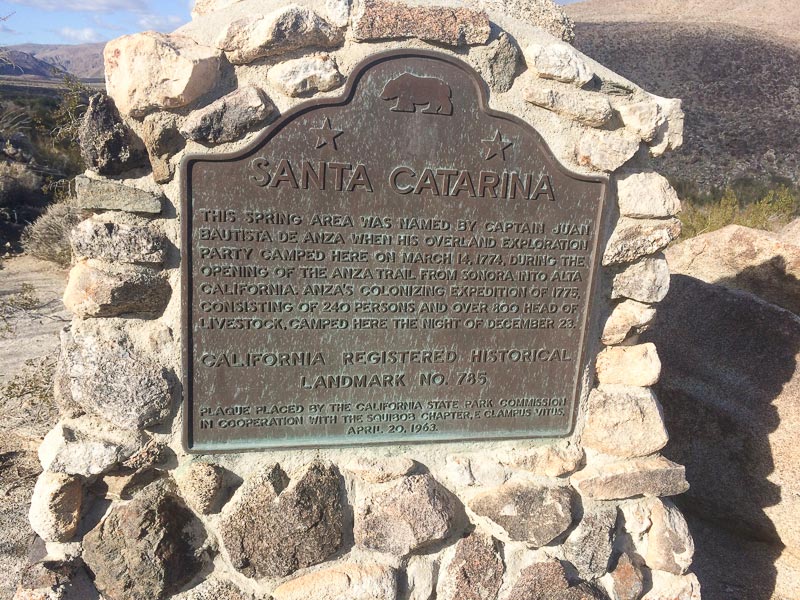

Every time I walk it (either up or down) I wonder when the huge boulder, in the picture above, is going to come crashing down. Hopefully it won’t be a time when I am in its path. Soon I am below Santa Catarina spring along Coyote Creek. I drink the last 8 ounces of water in my bottle and add 2 quarts of water to the empty bottle, and drop in a couple of water purification tablets in the process. From here my plan was to hike to Sheep Canyon for my 3rd night camp.

As I started up the Lower Willows Trail, I realized that after two full days of negotiating cross country obstacles I could just relax and walk an easy path enjoying the sights as I moved forward and not have to worry about thorns, spikes, rocks, or boulders.

Once I was past Lower Willows, Coyote Creek was dry. I was glad I got water below the spring, which normally runs year round. Soon I was in open country and headed west towards Sheep Canyon.

Reflecting back on 3 days of hiking, it occurred to me that I had not seen a single person. Sheep Canyon has a primitive campground that is accessible to 4WD vehicles – but it takes a pretty serious 4WD to get there. In the unlikely chance that there might be someone at Sheep Canyon Campground, I decided to stop short and make camp; I didn’t want to risk the wildness of this trip by seeing other people. The night was perfect. No wind and no rain. My headlight went dead just after dinner. That was okay. I sat outside with my quilt wrapped around me until probably midnight, just watching the sky.

DAY 4

I broke camp and headed back towards my truck. I decided to walk along the 4WD road towards 3rd Crossing, which is just below Santa Catarina spring. Where the road twisted around, I walked cross country. This is a route I had never hiked before and it turned out to be a great hike with views of the western canyons and everything to the east where I had spent most of the first 3 days. I ran into a side road with a sign that said historical landmark or something similar.

Where the road ended below the monument, I found a fully loaded backpack sitting next to the road. One wonders why or how someone left it here. Did they go for a short walk? Is it abandoned? Is there anything valuable in it? I left it alone.

Should you ever get to this spot and think you can get water, forget it. Santa Catarina is so heavily surround by vegetation, it would be just about impossible to travel through it. The brush would rip you and your gear to shreds.

After I took this picture, the camera was dead. I continued towards 3rd Crossing. Once there, I cut over to the trail through Ocotillo Patch, taking my time. Soon I would be back to the truck.

The end of almost every trip causes me some concern. That concern is: will be truck still be there? Will someone have vandalized it? It is sad these thoughts are real possibilities. Then I saw the truck. It was okay. I drove into the town of Borrego Springs and bought a cup of coffee from a surly lady in a convenience store. Was she nasty because I hadn’t had a shower in 4 days? Or is she just nasty person? Probably the later. This was the first person I had spoken to in 4 days, since I said goodbye to my wife. Too bad she had a poor disposition. I realized I was back in civilization.

I drove home and spent a day with Joyce before departing on the next adventure.