Fleece insulation has been a staple for backpacking and other outdoor pursuits since Patagonia introduced synthetic pile and then Synchilla fleece decades ago.

Over the past few years I have seen more and more articles comparing fleece to synthetic polyester batting material such as Polarguard, Climashield and similar materials as a better option to fleece.

These batten materials are lighter than fleece with an equal insulation rating, are more compact when packed, and the manufacturers state the material insulates when wet.

Sounds like a winner to me!

Or is it just hype?

Should We Make Purchase Decisions Based on These Laboratory Tests?

There is science (theory) and then there is the real world.

Yes, some of these fleece “replacements” are thinner, lighter, and provide more insulation per ounce compared to fleece. However, most of these replacement insulation pieces are analyzed independently of many other environmental factors.

Each of us has a physiology that is unique compared to others. In addition to physiology, our hiking pace, the difficulty of the trail (e.g., flat versus steep), what we wear under the insulation, and what we wear over the insulation impacts how well the insulation works for each individual. Combined, all these variable factors make laboratory testing difficult or even impossible.

How Should Fleece be used as Part of the Hiker’s Wardrobe?

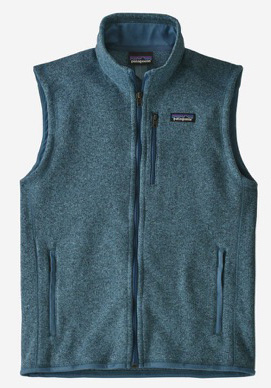

Fleece garments have become ubiquitous urban wear, often worn as outer insulation around town. But fleece, which was develop by Malden Mills (now named Polartech, LLC) and Patagonia, Inc., was designed to be used as an active insulation layer and a component of a clothing system.

Last year in this post on understanding layers, I took a somewhat comprehensive look at clothing layers and outlined the basic clothing system:

For backpackers the following layers are almost universally accepted as the best way to dress for the backcountry:

- Baselayer

- Active insulation

- Shell (wind and or rain)

- Insulated outer garment

Most of the time these are not all used at the same time. Weather, temperature, wind, level of activity, and the individual’s metabolism determined what layers should be worn under what conditions.

A brief summary from that post will note that baselayers (or contact layers as I like to call them) wick moisture from our skin. Our bodies, like a car engine, are somewhat inefficient, generating a lot of waste heat. A baselayer matched to the conditions and activity will wick away moisture and allow it to evaporate. In cold weather, too thin a layer will allow the moisture to evaporate too quickly making us cold, and too thick a baselayer will retain too much moisture also making us cold.

Fleece, as an active insulation layer is highly breathable. It comes in several thicknesses (100, 200, 300 are common identifiers) and also needs to be matched to the conditions and exertion levels. Keep in mind; fleece works best in cold, wet conditions.

Because fleece is so breathable, it does a poor job in windy weather and a lightweight wind shell is a valuable component of the clothing system.

If it is raining, then a waterproof shell can be substituted for the wind shell. I carry both — a wind shell and a rain shell — because a single “waterproof/breathable” shell is simply marketing hype. These garments are neither waterproof nor breathable as I documented in The Search for the Holy Grail: Waterproof Breathable Rain Gear.

To keep my fleece insulation dry in the rain, I use a highly ventilated poncho to shed rain.

Another Advantage of the Layering System Using Fleece

If it is too hot for your fleece, then take it off and just wear the baselayer or add a shell if needed. When wearing fleece, you can add a shell as the conditions warrant. The system has many combinations to mix and match.

People Wear Too Much Clothing!!

I have lived in a hot desert for over 40 years. As a result, I do poorly in cold weather. I do much worse in cold weather than all my friends I hike with.

But ironically, when hiking, I wear less clothing than my friends. They wear too much clothing, which can make it difficult to keep a body in thermal equilibrium.

For example, on a winter trip in the desert about 10 years ago, I hiked in shorts and a mesh tank top. Everyone else was wearing long sleeve shirts and pants. And yet, I am the one who gets cold easy.

On this same trip, the next morning was unexpectedly cold and windy. I started the day’s walking wearying a light down vest over a wind shirt and a baselayer. For the bottoms, I wore shorts over a baselayer. I planned (and did) to remove the down vest soon after we started our hike. Soon after that, I removed the baselayer bottoms and, again, hiked in shorts.

On another trip a few years ago, I had a similar ensemble — mesh baselayer for my top and shorts.

On this trip, my hiking partners were dressed quite a bit differently . . .

. . . and when we stopped at the end of the day, they were soaking wet with sweat and I was comfortably dry.

Keep in mind that I am not saying my way is better than how my friends dressed on these trips — they are all experienced hikers. Long sleeved shirts and long pants provide sun and insect protection that my choice of clothing did not.

My strategy is always thermal equilibrium first with an eye to bring no extra or extraneous weight in my pack.

The bottom line goal for each person should be a strategy that works for them, and recommending specific pieces of clothing for specific trips is an exercise in futility. What I do recommend is learning how a layering system works, and then assembling a wardrobe that will meet your needs for the specific conditions you will encounter. Unfortunately, this requires a bit of experimentation and experience.

Many experienced hikers have used the layer system with fleece as the active insulation for decades — in spite of what a laboratory test might suggest as better.

What if Your Active Insulation Gets Wet?

I have read many claims (to include manufacturers) that the batten type garments insulate when wet. A dubious claim at best. When water fills the air spaces in a material it cannot insulate.

I don’t know any manufacturer of fleece who claims it insulates when wet.

But what fleece does do is dry quickly via excess body heat. If for some reason your fleece gets wet, take it off and wring out as much moisture as possible, put it on and start hiking. Use a shell in conjunction as the conditions dictate (e.g., wind or rain shell). If you have the correct thickness of fleece for the conditions, it will dry quickly from the heat your body generates. But you have to generate heat — sitting around in a wet fleece top won’t dry it out.

Advantages of Fleece

It is robust. Unlike the batten insulations, it doesn’t lose its insulating properties over time. I have fleece garments that are decades old. Fleece is inexpensive, unless you purchase brand names at retail prices. Discount stores sell fleece tops for under $20. Thrift stores sell fleece tops that are in great shape for about $10.

Unlike the batten insulation garments that must have an inner and outer fabric covering, you can add a shell as needed. Batten garments come with a shell material, which you cannot remove.

Fleece in Action

From the post on understanding layers I linked to earlier, these are my typical layering systems for various conditions with the minimum temperature I expect at night in camp: