So we got home from our end-of-summer camping trip on September 20th, or two days before the official end of summer, which marks the beginning of autumn. I like to call it autumn because that name is derived from an old Latin word, autumns. Autumn entered the English language about 700 years ago.

Of course when we think of autumn, changing colors in forests and the falling leaves often come to mind. Poets often wrote about this colorful season and soon it was referred to as “the falling of leaves.” So about 500 years ago, in the English language, this was changed to simply “fall.”

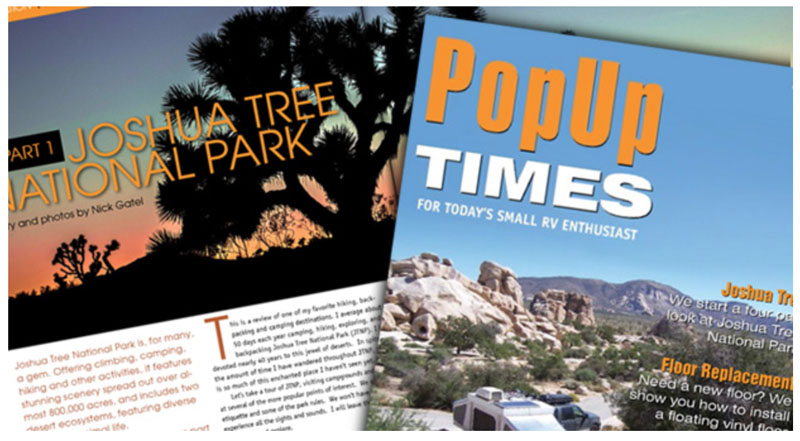

In the desert, unless there are cottonwood trees nearby, there isn’t a “falling of leaves” during this time of the year. But there are balmy nights, and the night sky becomes darker and clearer. So with this in mind, I headed to the high desert a few days after our trip to Lake Mead.

Continue reading The First Camping Trip of Autumn — or is it Fall?